One week to go!

We are really gearing up to start welcoming you back to John Muir’s Birthplace from Tuesday 18 August. Our screens have now been installed to keep both visitors and staff safe, and we will be laying floor stickers to help with social distancing. We are also working closely with our staff this week to devise new cleaning regimes, and we recommend that anyone wishing to visit to prebook their time by emailing museumseast@eastlothian.gov.uk or calling 01368 865899 as we will be limiting the amount of people in the building at one time.

Our opening times from 18 August will be Tuesday – Saturday 10am – 5pm – we can’t wait to welcome you back!

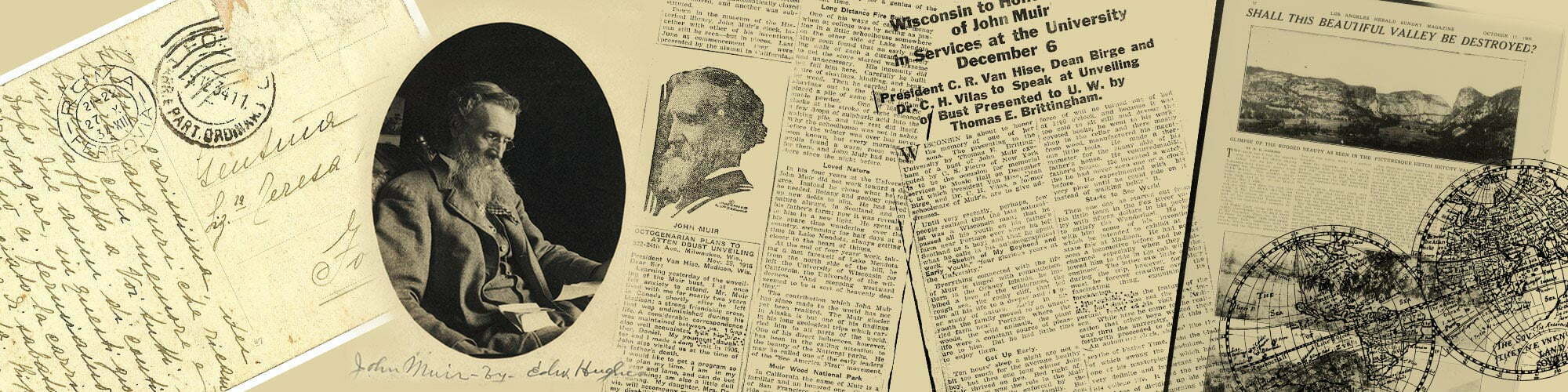

This is the final post looking at the story of John Muir’s Dunbar homes. This account focuses on the development of Dunbar’s rediscovery of John Muir and the creation of a fitting tribute within the shell of his birthplace.

So far in the process of uncovering the history of these buildings we’ve touched on stories of war and empire, of tensions between generations, and, in particular, the story of one wee Dunbar laddie whose tale now strides continents. But fifty years ago, you’d have been hard put to find anyone in Dunbar who had heard of John Muir!

Muir Rediscovered

We left our tale of John’s Birthplace in the 1920s. With the passing of years, and the passing of his last relatives and friends in Dunbar, local awareness of John’s career and significance was lost from common knowledge. It took a trickle of American visitors to begin the process of rediscovery!

The first arrivals came on the back of an initiative in Martinez, California. There, a group had formed to ensure a fitting memorial to California’s greatest son and to preserve his marital home as a monument for future generations. Harriet Kelly of Martinez is still remembered in Dunbar. She visited twice in the early 1960s and enlisted the help of Dunbar’s town clerk and other locals to uncover some of the forgotten story, linking John’s writing and photographs to the places that they belonged.

John Muir’s Birthplace c1997 (© Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk)

Bill and Maimie Kimes, Muir biographers, made more connections when they visited in 1967. They made a disciple in Frank Tindall, then the County Planning Officer, who helped them ensure that the Birthplace was marked with a fitting plaque. A few years later Frank was able to convince the Hawryluk family, the proprietors of the building, to abandon plans to convert much of it from a dry-cleaning facility into a fish restaurant. Frank and another local official, Ian Fullarton, were able then to lease the top floor of the building for a small ‘tribute’ to Muir – some re-imagined rooms and an audio-visual presentation. This opened in the early 1980s managed by East Lothian Tourist Board, who staffed it seasonally. And so it remained into the early 1990s. Then a new proposal surfaced.

John Muir was becoming much more widely known in his homeland. Connections between Dunbar and Martinez had been forged. The John Muir Trust had begun its work ‘to defend wild land, enhance habitats and encourage people of all ages and backgrounds to connect with wild places’. And East Lothian District Council floated an idea to build a ‘John Muir Centre’ within John Muir Country Park to pick up that theme.

This idea came to nothing but it stimulated local discussion and a new beginning.

John Muir’s Birthplace today

There had been enough knowledge, as we have seen, to establish the first ‘Muir Museum’ on the top floor of his renovated birthplace. The baton was picked up by Dunbar’s John Muir Association in the 1990s. To realize their ambitious plans a lot more groundwork was done. Not least, in exploring John Muir’s Dunbar and finding the hidden paths that John surely trod – to school, to church, on excursions with Grandfather Gilrye. This process, aided greatly by John’s own written accounts, began to uncover other facets of both buildings. The Association’s efforts culminated in success. A new multi-partner trust was formed to purchase the building and seek funds for its development and a ‘new’ Birthplace Museum opened in 2003. It incorporates all of the building’s structure that had survived the impulses of multiple owners since the Muirs left and it addresses Muir’s story for a contemporary audience. Over 200,000 visitors have passed through the doors since it opened.

Our Work Continues

Meanwhile, discovery has proceeded apace. One of the driving forces has been our visitors themselves. We are often asked about the buildings; we are sometimes told of family associations relating to other occupants; we are sometimes told of a snippet about the buildings we didn’t know. But the main thing is that we don’t like to be stumped!

The creation of East Lothian’s new Archive & Local History Centre above Haddington Library in the John Gray Centre was another stimulus to research. All at once there were untouched sources readily available! In fact, one of us used a secondment there to provide the bare bones of a house history:

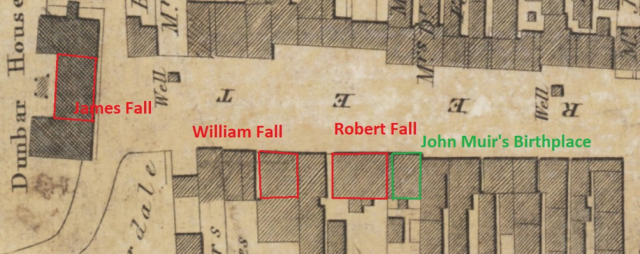

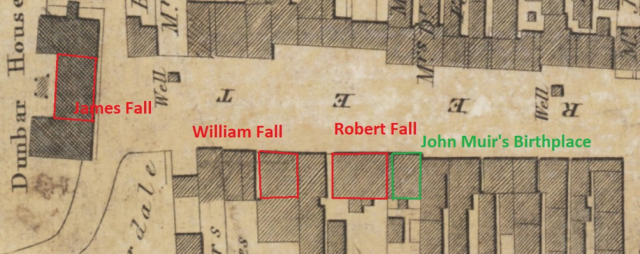

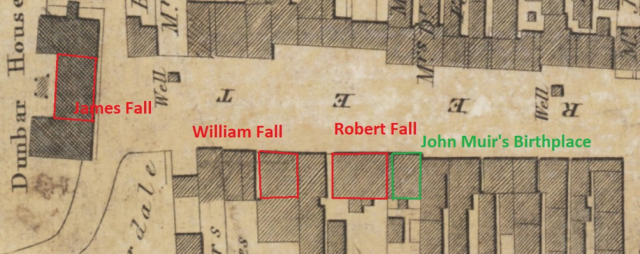

These pages formed the framework to this series of blogs – although we’ve gone into much more detail here. They take you through the steps of unearthing any urban Scottish house history, although resources available differ from place to place. Of course, since the pages were written, the Internet has grown apace. It is relatively straightforward today to access digital copies of primary sources that were simply not available ten years ago. We are fortunate because many of the inhabitants of the two Dunbar house associated with the Muir family had unusual surnames – Fall, Delisle, Wightman – and, as it turns out, include some significant characters – Philip Delisle of Calcutta, Dr Charles Wightman of Newcastle.

However, it is harder to say much about the people that lived in the Birthplace and its neighbour in the Victorian period. Where did Mrs Fish the teacher come from? And who attended her school? For this kind of detail we’re much more reliant on other family historians and people that pop though the door.

So, if you have made a connection through our blogs, or have a story to tell us – please do! We’ll be opening again on 18 August and we’d love to see you, to chat, and to share stories.

We are very excited to be busy cleaning and preparing to finally welcome you all back on Tuesday 18 August. Things will be a wee bit different. There will be some changes to how we do things and we will let you know about these in the next few days. Initially we will be open Tuesday to Saturday 10am to 5pm. Visits will still be free of charge, but we do ask you to email museumseast@eastlothian.org.uk to book your visit. We look forward to seeing you all soon!

This is the second post looking at the story of John Muir’s Dunbar homes after the Muirs left for America. The amount of detail available grows – as does the pace of change in both ownership and occupancy. This post focuses solely on John Muir’s childhood home, next door to his birthplace, now 130-134 High Street.

The Muirs Move On

We left John Muir’s childhood home at the beginning of February 1849 after Daniel Muir sold the house to Dr John Lorn and the Muir family set off to a new start across the Atlantic.

Dr John Lorn bought the property for himself and his mother; they had been living with relatives in Dunbar for some time. Janet (Jessie) Simpson Lorn had first left Dunbar in 1813 when she married John Lorn senior, a merchant, mariner and shipowner of Grangemouth, a port much further up the Forth than Dunbar. But Jessie was was widowed in 1821 at the age of just 33. She was left with two young children – but a good estate held in trust by her husband’s will. She and the children (John born 1815, and Ann, born 1819) made their home in Dunbar during 1830 – Ann Gilrye Muir was their near contemporary.Young John trained in medicine at nearby Edinburgh, becoming a licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons in September 1836. His sister Ann moved away when she married Dr John Moir a couple of years after, but John never married. Instead, he and his mother made the Dunbar house their home. John never seems to have taken his medical practice too seriously – lawn bowls and the management of the Free Kirk were more his thing. After his mother died in 1866 he spent less time in Dunbar – the house was let to a Dr David James in 1871 and was sold the following year to William Brodie, a Dunbar businessman. Dr John retired to Edinburgh’s new town where he purchased 27 Drummond Place and died there in 1888.

A New Venture – the Lorne Hotel

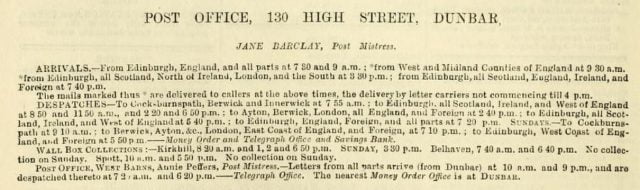

William Brodie’s purchase of the house was with a specific object in mind. Dunbar was a rising holiday destination and a new kind of venture was all the rage – the Temperance Hotel. Aimed specifically at families rather than the commercial market, temperance hotels were exactly that – alcohol free premises! Astute businessman that he was, Brodie also redeveloped the ground floor of the building to create two shops. This would provide a steady income if the hotel proved unpopular. The one to the south was snapped up by an extremely reliable tenant – Dunbar Post Office under Miss Jane Barclay, moving out from John’s birthplace next door. It remained so until 1904. The other went with the hotel, being variously used as offices or tea-rooms.

The busy Dunbar Post Office, 1889, in John Muir’s Childhood Home

Brodie’s venture was open for the summer of 1872 under the management of Thomas Wilson and then from 1875 by Eliza Hannan. When William Brodie died his trustees then let the upper part of the building to a Mrs Margaret Fish and her daughters who started a private school in their part of the building. Then in 1886 the hotel reopened under John Henderson and his wife for a few years followed by Thomas Thomson. Both Henderson and Thomson ran tearooms and a confectionery outlet from the ground floor of the building.

It was during Thomas Thomson’s tenure that John Muir revisited Dunbar. He wrote to Louie, his wife:

There was no carriage from the Lorne Hotel that used to be our home, so I took the one from the St. George, which I remember well as Cossar’s Inn that I passed every day on my way to school. But I’m going to the Lorne, if for nothing else to take a look at that dormer window I climbed in my nightgown, to see what kind of an adventure it really was.

John Muir’s Childhood Home around 1893. Courtesy University of the Pacific. Copyright Muir-Hanna Trust

John found the dormers still there: he was keen to see the site of one of his childhood ‘scootchers’ or dares. After being put to bed one night, he and brother Davie had ventured out the window, onto the roof, each challenging the other to go further!

Shortly after Muir’s only return home, the building was in 1896 purchased from Brodie’s estate by Henry Huntly, formerly of Dunbar’s Jersey Arms Hotel. Huntly ran the hotel himself, although perhaps not successfully: one of his first moves was to apply for a liquor license, which was refused.

John Smith, a Dunbar baker, bought the building in 1902. At first, the Smiths leased out the hotel (interspersed with periods of self-management). Similarly the former post office was taken by Henry Davidson, a shoemaker. In the early days of their tenure only the shop on the northern side was continuously in their own hands, an outlet for their bakery produce and tearooms. As time passed more and more of the Smiths’ business was transferred to their new premises. As before, sometimes they operated the Lorne Hotel ‘in-house’; sometimes it was leased, or under management. By the late 1920s, the next generation built a bakehouse behind the building, in a part of the Muirs’ old garden. When Davidson’s lease expired the southernmost shop became Smith’s bakery, which became a Dunbar institution through into the 21st century!

Next Time

We’ll bring the story to a close in the present day – and explain a bit more about how we dug up the history of John Muir’s houses in Dunbar.

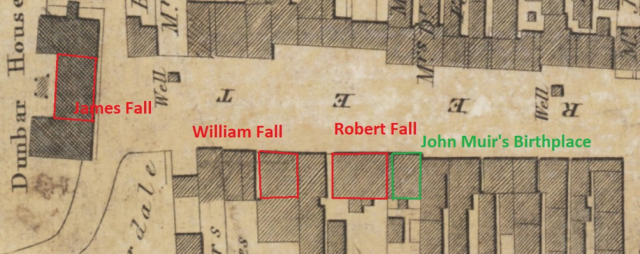

Our next couple of posts will look at the story of John Muir’s Dunbar homes after the Muirs left for America. These homes comprise his birthplace, which now houses the museum, and his childhood home next door which his father bought in 1841. This is the building that John remembered. The amount of detail available grows – as does the pace of change in both ownership and occupancy. This post focuses solely on John Muir’s Birthplace, now numbered 126 High Street.

Daniel Muir Moves On

When Daniel Muir moved his family out of the original room behind his shop he kept the tenancy of the building – or at least, he was the named tenant for the residual Wightman estate. In 1841 the building was occupied by:

on the ground floor, John Finlay a retired sea captain, his wife Catherine, their daughter Margaret and granddaughter Marion Runciman. John Finlay was trading as a spirit dealer from the shop. It may be that Finlay was one of the ‘old sailors’ who the boys of Dunbar enlisted to sort the sails and rigging of their toy boats, as recounted by John Muir. He was certainly handily placed for John and Davie. Odd to think that this old sea-dog in his little grog-shop was the grandfather of a Baron and great grandfather of a Viscount!

on the middle floor, James Low, a blacksmith, and his family – 12 people in all!

on the top floor, George Jeffrey and his family – 5 people.

That’s a total of 21 people resident in what is now the John Muir’s Birthplace Museum, in three distinct households but with no real amenities – neither running water, gas lighting or even an indoor toilet!

The next event in the building’s tale came in 1846. Still desperate for money Dr Wightman sold the house to Matthew Watt of Belhaven (Wightman’s financial difficulties would be common knowledge). Watt had been a hand loom weaver but, as that profession was driven out of the market by mechanisation, had opened a successful grocery. He bought the house as an investment and continued to live and trade from Belhaven.

Matthew owned the house until he died in 1874 at the age of 80. In 1877 his estate sold the house to a sitting tenant, the postman Peter Aitchison, marking the start of a period of rapid turnover. Betsey Anderson owned it in 1878, William Fraser in 1879, William Rennie in 1883, and Daniel Smith in 1885. Smith’s purchase marks a return to stability: it remained in his hands, then his heirs, until 1924.

Who Lived in the Birthplace

It’s impossible to list all the inhabitants of the Birthplace, so we’ll highlight just a few. A stanza from an old Dunbar song or rhyme helps us to begin:

‘And a’ our great worthies are sure to be there

‘In summer, or winter, be it foul, be’t fair

‘Matthew Watt, Willie Howell, Willie Liddle would drop,

‘In tae hear a’ the news in John Cockburn’s shop.’

Matthew Watt we know: he owned the building from 1846; Willie Howell, a bookbinder to trade, lived with his family on the top floor from around the time of Matthew’s purchase to his death in 1879; John Cockburn, whose saddlery is celebrated in the song as a great place for chat and gossip, occupied the middle flat between 1861-69. It’s pretty clear that Matthew preferred to let to his friends.

After the Howells, the top flat was rented by Alexander Thompson (a tailor) and family; Staff Sergeant Flowett Marshall (serving with the staff of the local volunteers) and family; John Robertson (a (horse-drawn) vanman) and family; and then into the 20th century with Walter Brydon (a gardener) and family.

Down below them, after John Cockburn moved to Edinburgh, the middle flat was rented by John McCliskie (ropemaker) and family, John Frame (a groom who subsequently worked as a grocer) and family, the carter Alexander Dickson and his family; and then the labourer Martin Jewels and his family.

John Muir’s Birthplace around 1890; note Black’s shop (cropped from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Muir_birthplace.jpg)

Below them the shop saw some transformations. There’s a gap in the records after John Finlay until the financial year beginning April 1857. It then became Dunbar Post Office when Miss Barclay took up the lease. The PO had been nearer the West Port under Miss Barclay’s father, the previous Postmaster. This change saw the shop quickly revalued from £7 to £10 annually, so there must have been significant work carried out; perhaps gas lighting was then installed. In 1872 Miss Barclay sub-let the premises to a Mrs Hannan when the Post Office relocated again, then Peter Aitchison occupied the shop for some years (the first owner occupier in the house’s history). His successor was William Fraser, another owner-occupier and Dunbar harbourmaster, who seems to have set the shop up as a grocery but mostly sub-let its operation. Andrew William Anderson, a clock and watchmaker newly arrived from Dundee, lived with his family in the Muirs’ old quarters for three years as he was establishing his business in Dunbar. He was followed in 1889 by William Black (and his sister) who had a drapery through until 1916.

Next Time

What happened in John Muir’s childhood home after the family emigrated?

In this blog we consider what happened to Dr Wightman, who had left a roomful of chemistry apparatus in his house in Dunbar but who lived far away in Northumberland. And the Muirs make their moves.

The Travails of Dr Wightman

Title page of Charles Wightman’s ‘Treatise’ (from archive.org)

After he graduated from Edinburgh University and set up as a physician in Alnwick, Dr Charles Wightman seems to have prospered. He soon moved to Sunderland and then to Newcastle-upon-Tyne where he bought a fine house in a good location. Along the way he married (1822) Miss Janet Thomson, a daughter of the laird of Earnslaw in Berwickshire, and began a family. His inheritance was invested in property, land and the stock market – it’s fair to say he went potty about the railways that were being floated in the 1830s. He subscribed £5000 to each of at least 5 separate railway flotations (not all these came to fruition, so the same sum might be invested more than once)! In 1840 he published a Treatise of the Sympathetic Relation between the Stomach and the Brain, which indicates his professional interests.

But fortune turned. The early railway speculations were a bubble and many investors lost out – Dr Wightman amongst them. While his speculations were in play, his family was decimated by death. He lost his wife and several children until, In 1841, at his fine Georgian residence in Eldon Square, Newcastle, only he and his daughter Janet Thomson Wightman were left. A housekeeper and two other female servants completed the household. Dr Wightman made several public (and fawning) attempts to be appointed Physician to Newcastle Infirmary, but was never preferred. He tried for other public medical posts, without success. The Newcastle house, and land he had purchased speculatively, had to be mortgaged. It would seem on top of everything that money troubles were growing. Even the houses in Dunbar were sold. Robert Fall’s old house went to Daniel Muir in January 1842 and the ‘new built house’ (where John Muir was born) to Matthew Watt during 1846.

In 1847 a mortgage on the house in Eldon Square was transferred to a local painter and decorator (in lieu of debt?). By the census of 1851 Dr Wightman was resident in a lodging house in Princes Street, Newcastle; his landlady was his former housekeeper.

Dr Charles’ surviving daughter Janet, however, made a good match. In 1853 she married Alexander Christie-Thomson, controller of the Post Office Savings Bank, then on its way to becoming a national institution. But Dr Charles died in Newcastle during 1857. There was nothing left for Janet to inherit.

Daniel Muir Advances

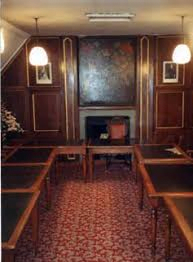

Re-imagined interior of John Muir’s first home (Image by CyArk for JMBT & Partners)

Daniel Muir arrived in Dunbar with a new wife, a lease on a house, and took over a struggling business. He lost the first, kept the second, and transformed the third.

A simple way to monitor Daniel Muir’s progress is to tap the opinion of the Session Clerk who compiled the Parish Register. Until David Muir was born in 1840, Daniel was described as ‘shopkeeper’ at the baptisms of his three earliest children; with David it became ‘mealmonger’; with Daniel junior ‘mealdealer’; and finally, with the twins in 1846, ‘merchant’. Daniel had made it in the eyes of Dunbar officialdom!

As Daniel progressed though the ranks of Dunbar society, revolution was in the air. Years of burgess privileges had been swept away in the Reform Acts of the 1830s. For Daniel and his like minded friends in the Associate Presbyterian churches it meant enfranchisement for many. Whereas David Gilrye, Daniel’s father-in-law, had been eligible to sit on the burgh council simply because he was a burgess, Daniel was now eligible as a simple elector in a much expanded electorate. And stand he did.

Council Chamber, Dunbar Town House

The council had been reduced to 12 elected members, 4 being elected (for a 3 year term) every October. It took some years for the ‘new men’ (it was still only men) to become a majority. When they did, the council went from Tory to Whig (Liberal). In October of 1847, when Daniel joined the council, Simon Sawers of Newhouse (a former civil administrator of Ceylon (Sri Lanka)) became provost (mayor) in the Liberal interest and Christopher Middlemass, who had dominated Dunbar politics in the Tory interest for the best part of 50 years, found himself an ordinary councillor sitting alongside the likes of Daniel Muir, John Mather (Ann Gilrye’s cousin), John Richardson (father of John’s friend Bob), and Robert Cossar the innkeeper, all newly enfranchised ‘new men’.

Daniel was obviously a good man to cultivate. With his rising status amongst the businessmen of the town, his reputation for ‘fair dealing and good measure’, his forthright Christianity and generosity to his chosen church he would be noticed. It would be noticed too that he had purchased ‘that large and commodious house’ that John remembered. Daniel had bought the house from Dr Wightman’s agents when the Doctor’s money needs became imperative in January 1842. But the evidence suggest that the family was already in occupation before that date.

A decennial census was taken on the night of 6th June 1841. The information is scanty – named household members, occupations, ages and an indication of birthplace – and addresses minimal, but it is clear that the Muirs (spelt Moore by the census taker) are in the big house. The gardener’s widow Catherine Nisbet, still in residence above the laundry on the north side of the garden, is named immediately before the Muir family. Dr Wightman, despite his own circumstances, took care to ensure that her liferent right to the cottage was written into the terms of the sale to Daniel. As the census shows that the ground floor of John’s birthplace next along the street was occupied by John Finlay and his family, Daniel had moved his growing business to the big house as well.

Another snippet of evidence perhaps corroborates the Muirs’ occupation of the house prior to purchase and it comes from John Muir himself. John related that sister Sarah tipped little John off his stool such that he bit his tongue. Then he was rushed out the back way, through the garden to Peter Lawson, the apothecary. John estimated he was then around 2 ½ – say between October 1840 and January of the next year, when he started school. This can only have happened from the big house – there was no back route from the wee house.

The next change for John Muir’s childhood home came at the beginning of February 1849. Daniel Muir sold the house to Dr John Lorn. Daniel, Sarah, John and David began their journey to America before the end of the month. Ann and the rest of the children may have been in residence until they left in October, or they may have moved back in with her parents over the road. A new start for all.

Next Time

The houses after the Muirs – the Victorian years.

In the last blog we left the Muir houses in the hands of the absentee owner Doctor Charles Wightman, who was resident in Northumberland. We’re still in that awkward phase where records are scanty, but the situation is improving.

Who Lived in the Houses?

Two snippets help to fill in some of the detail about what happened next. With the Nisbets (John and James) in possession of the large garden, the big house was let out to a succession of generally wealthy (it can be assumed) tenants. Mostly this was easily arranged by word of mouth but in 1821 Dr Wightman’s agents had to advertise. The advert shows that the then tenant was William Sandilands of Barneyhill, a former captain in the 7th Dragoons and a ‘gentleman farmer’. It’s worth showing the advert in full for the details it gives of the house:

House, gardens, etc., in Dunbar to be let.

To be let for one or more years as may be agreed on, and entered into immediately. That large and commodious house, in the town of Dunbar, belonging to Dr. Wightman, and presently occupied by Mr. Sandilands, with two good gardens, stables, and coachhouse. The house is well calculated for the accommodation of a genteel and numerous family, consisting of parlour, dining room, drawing room, and five excellent bedrooms, with a light bed closet to each of them, besides four garret rooms, kitchen and servant’s room, cellars and other conveniences. The house, stable and garden, immediately behind it, may either be let separately or along with the coachhouse and the other stable and garden, as may be agreed to. For further particulars apply to Mr. Turnbull, surgeon, Dunbar, or to Mr. Sievwright, 102 South Bridge, Edinburgh.

Edinburgh Evening Courant, 17 December 1821.

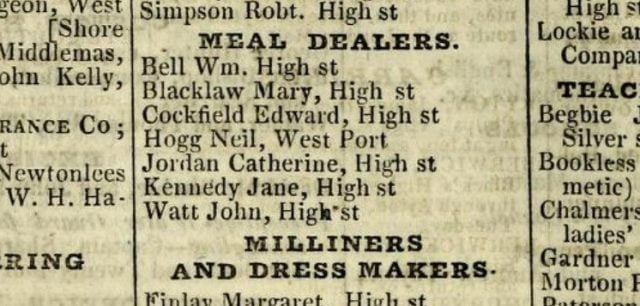

Pigot’s Directory of 1825-6 gives us our sole clue for the other house in this period, and that’s only by working back from the account that John Muir left:

Jane, or Janet, Kennedy occupied John Muir’s Birthplace and traded as a ‘mealdealer’; there is no information about the other tenants on the upper floors. We don’t know if there had been other tenants between her and Joseph Hogg the tobacconist.

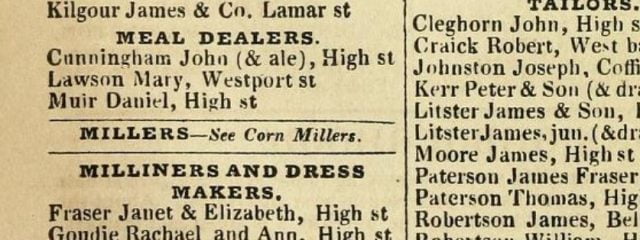

Now, mealdealer – that’s a fairly specific occupation in a 19th century Scottish context. It meant ‘one who dealt in oatmeal’ – an essential component of the Scots’ diet but also an essential commodity in a town like Dunbar where there were many draught, carriage and riding horses stabled. Note that the demand for meal could accommodate seven separate businesses for a population of around 3000.

Daniel Muir Comes to Town

From now on the sources for the two houses become much greater. In his obituary of his father John Muir wrote:

‘Going to Glasgow and drifting about the great city, friendless and unknown, he was induced to enter the British Army, but remained in it only a few years, when he purchased his discharge before he had been engaged in any active service.

‘On leaving the Army he married and began business as a merchant in Dunbar, Scotland. Here he remained and prospered for twenty years; establishing an excellent reputation for fair dealing and enterprise’.

Discussing the same events in the Life and Letters of John Muir, William Frederic Bade wrote:

Daniel Muir, coming to Dunbar as a recruiting sergeant, met there his first wife by whom he had one child. She was a woman of some means and enabled him to purchase his release from the army in order to engage in the conduct of a business which she had inherited. Their happiness together was of brief duration, for both she and the child were snatched away by a premature death, leaving him alone.

There’s not a lot of detail to work with there, but let’s have a stab at filling it in.

Daniel and Helen

Mrs Janet Kennedy’s Grave (Image courtesy Dunbar and District History Society)

Mrs Janet Kennedy died at Dunbar on the 18th of February 1829: a point to note is that she was given the title ‘Mrs’ and her married surname in the Old Parish Record entry. That marks her as being above the ‘common class’. She had a son Thomas Kennedy, a sergeant in the Royal Artillery, who arranged for a headstone to be erected over the grave in the kirkyard.

Janet also had a had a daughter ‘Helen’ whose name came down to John Muir as ‘Helen’; and so she is recorded when she died and was buried at Dunbar in 1832. The entry in Dunbar’s old parish register shows Helen was Daniel’s first wife; but there is no corresponding marriage record at Dunbar. So, how did Daniel meet Helen and come to Dunbar?

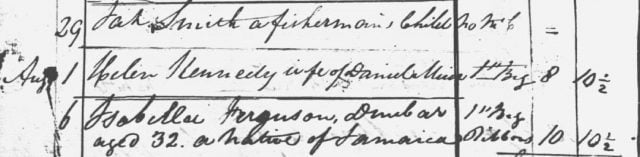

Helen Kennedy, Dunbar Old Parish Register of Deaths. (National Records of Scotland from ScotlandsPeople.gov.uk)

Well, Sergeant Thomas Kennedy was stationed at Berwick-upon-Tweed, around 30 miles to the south of Dunbar. A notice in the Berwick Advertiser, an entry in Northumberland Records and also the Records of Cross Border Marriages show the marriage of Eleanor Weatherlie Kennedy, spinster of Dunbar, and Daniel Muir, bachelor of Berwick, a Scot and serving soldier in the Royal Artillery. The date was 07 October 1829. It would appear that Sgt. Thomas Kennedy and Daniel were in the same unit, making Thomas the likely means of their introduction. For eight months Helen, or Eleanor, had been in charge of her late mother’s business in Dunbar. It was a relatively simple matter for Daniel to take over after they married. He then set about building the business to the state John Muir recalled. Now settled, he began to leave a documentary record:

… Daniel Muir, shopkeeper and tenant, house and shop on the west side of the High Street of Dunbar…

Dunbar Voters Roll, 1832-3, John Gray Centre.

And in Pigot’s Directory of 1836-7 Daniel replaces Janet Kennedy in the list of mealdealers:

The young couple did not have long together. As noted above, Helen died on 01 August 1832. There is as yet no evidence of a child of the marriage, then living or dead, despite Bade’s assertion. After a decent interval, Daniel remarried. His spouse was the young Ann Gilrye who lived a few doors away on the other side of the street. Daniel and Ann were married at Dunbar on the 17th November 1833. Daniel was 29 and Ann was 20 years old.

Next Time

What on earth happened to Dr Wightman? Daniel Muir wins a reputation and buys a house.

In the last blog we explored lives of the Delisle family during their tenure of John Muir’s childhood home. In this blog we need to introduce a new building – John Muir’s Birthplace (finally).

An End and a New Owner

At the start of the last blog, we had reached a point where the big house was a very busy place. It was occupied by Mary Melvil Fall Delisle, and the four children of her stepson Philip Delisle II. Mary had two (unnamed, unfortunately) servants living in the house to help. But we skipped past some details to explore the fate of these children. We need to jump back a few years.

The earlier event of note was the death of Janet Fall Barton in Ireland in 1768. As she was childless, her will stipulated that her property in Dunbar went to her mother Mary Melvil Fall Delisle, and the will was proved by 1775. So, the house that she had lived in all these years was now Mary’s own. Perhaps it was the death of her own stepson Philip Delisle II and her own advancing years, that prompted Mary to prepare her own will. It was witnessed and registered during 1789. Three years later, on 10 October 1792, she died, bringing to an end the Fall phase of the house’s story. She had, however, taken steps some years before her death to ensure a reliable income in her last years.

Building the Birthplace

In Janet’s will (1768; and also at the time of its proving in 1775) there is no mention of the building later possessed by Daniel Muir, the house where John Muir was born. But in Mary’s will a ‘new-built house in the south end’ (of the big house) appears. By the 1780s Mary no longer needed to keep a carriage. The redundant entranceway was just big enough for a small tenement building. Its purpose was to provide Mary with a steady income from the rent so it would appear that this was done between 1775 and 1789, probably much nearer the latter date. Ann Delisle Wightman inherited both properties on Mary’s death in 1792. At this early date, it is extremely difficult to tell who actually lived where. Not until 1855 is there an annual register that provides that fine detail. But sometimes there’s a glimmer. When Ann proved Mary’s will in 1792 the ‘new-built house’ was possessed (tenanted) by ‘Joseph Hogg and others’. Therefore Joseph is the first known occupant of John Muir’s Birthplace.

The New-Built House (cropped from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Muir_birthplace.jpg)

Joseph Hogg was a councillor and bailie of Dunbar and he played the same role in the house as Daniel Muir did in later years – he was the named tenant who sublet the apartments on the upper floor and rendered the rent due from the whole to the owners. His own residence was elsewhere but he may have run his business from the ground floor. He was a tobacconist, another person with a strong interest in the ‘free trade’ endemic at the time!

The Wightmans

Meanwhile, it’s time to consider Ann Delisle and the Wightmans. Charles Stewart Wightman and William Wightman were the oldest sons of Charles Wightman of Anstruther. The older Charles was one of history’s characters – bon vivant, clubbable, an ardent Jacobite, and wealthy. From the Castle of Dreel in Anstruther he combined business as a merchant with duties as factor to the estate of the earls of Kellie. But everyone, not least the Excise, about the Firth of Forth knew him to be a great supporter of ‘free trade’ (another one!). In short, he was a significant clandestine receiver of the untaxed goods brought to the Forth in the ships of the major smugglers – most certainly including our old friends, the Fall brothers and their heirs in Dunbar. His first son seems to have been a chip off the old block and was also a reputed smuggler, and that was probably why he relocated to Eyemouth. But the younger Charles’ main interest lay in the Caribbean where the family had invested much of their profits. That story takes us too far from Dunbar, so lets get back to Ann and William Wightman.

Dr William seems to have ‘minded the shop’ for his brother as well as practising medicine in Eyemouth. From Eyemouth also, Ann & William could keep a close eye on doings in Dunbar. And also keep a close eye on their perceived rights, as Ann did when she challenged her nephews’ and nieces’ inheritance. Ann and William had three children at Eyemouth during the 1780s:

Philip Delisle Wightman in 1785, named after Ann’s father (and brother)

Isabel Wightman in 1786, named after William’s mother

Charles Wightman in 1788, named after William’s father (and brother)

Surviving correspondence shows William at work in Eyemouth through to 1788, but then there is a gap until 1806 when his address is Dunbar. We must assume that when Ann inherited the house in Dunbar in 1792 that they relocated; whether the four children left by Philip in Mary’s care were still there is a moot point but is likely that they were. Very likely they were now Ann and William’s responsibility. We lose track of Philip and Isobel Wightman, but young Charles continues the story.

After completing his education (probably) at Dunbar Grammar School, Charles went up to Edinburgh University in 1810 to study medicine (following in his father’s footsteps: William Wightman was there in 1769-70). Not long after he graduated, first his father William (September 1816) and then his mother Ann (April 1817) died. Both houses now belonged to young Doctor Charles Wightman: his father’s will confirms Charles as the only child ‘now in life’. He also got £1000 as soon as his father died and a subsequent £3000 was earmarked for him when his trustees had sorted the estate. A not insignificant sum in 1816!

What of the houses? All four of Charles’ cousins had left Dunbar (or died; see last blog). He himself began his medical practice in Alnwick, Northumberland. Independently wealthy, Charles hardly needed the rents from the properties but from this time both were leased: the new house to a succession of local tenants; the big house to more wealthy ‘residenters’ – people of independent means. The garden was leased separately to James and John Nisbet who worked it as a commercial market garden.

Next Time

With Dr Charles Wightman an absentee landlord in Northumberland, what happened to the Dunbar houses? Find out in our next instalment.

In the earlier parts of this blog we looked at the first family that built and lived in John Muir’s childhood home. We begin this blog with a new family and their story.

Robert Fall’s house became the property of his daughter Janet Fall Barton

The Second Family

After marrying her soldier John Barton, Janet Fall seems to have split her time between Dunbar and Ireland. She was still in Dunbar in 1752 when she became a founding investor in the Lothian and Merse Whale Fishing Company, the latest scheme of her cousins in the family business. She was back again in 1758. Sadly, John’s death was recorded at Dunbar on the 17th of July, which seems to have prompted Janet to write her own will, registered in November 1758. This may have been in part to sort out her mother’s security. Janet still owned the house but her mother and her new step family were now the principal residents. Janet never met the next group to arrive: she died in Ireland during 1768.

Captain Philip Delisle continued as a serving officer, so his second wife Mary Melvil Fall must have been left with her hands full looking after her step-children Elizabeth, Philip junior and Ann Delisle. There were nursemaids and servants to help but still, feeding, clothing and schooling the children must have kept Mary busy. She did well and all three reached adulthood. They began to make their way in the world:

Elizabeth Delisle married Thomas Meek in September 1779. Thomas was a local merchant, much involved in the management of the Whale Fishing Company. The couple remained in Dunbar where Elizabeth died in 1791.

Philip Delisle junior joined the East India Company’s army in Bengal. He was dead by 1788, but therein lies a tale!

Ann Delisle eloped with Dr William Wightman of Eyemouth. Their irregular marriage was registered at Haddington in August 1782. They settled in Eyemouth where William practised and his brother Charles Stewart Wightman was a prominent merchant and more!

Philip junior’s Tale

We’ll take some time to look at Philip’s tale, as it bears on the later house history. In 18th century Scotland the British East India Company, the semi-government institution that monopolised Britain’s trade with the sub-continent, was seen as a wonderful career opportunity for adventurous young men. The plum administrative positions with the company were the very devil to get. It needed connections and political influence to secure even a minor clerkship. But there was another, much easier way. There were always openings in the Company’s armies, such was the attrition of the officer corps through disease, debilitation and death – comparatively few died in battle. But if chance allowed survival, there were opportunities aplenty. That’s the route young Philip took. As yet we know nothing of his military career except that, like his father, he reached the rank of captain. Between 1775 and 1782 he was deputy Paymaster to the 1st Brigade of the Company’s Army stationed at Fort William, Calcutta. His activities become much clearer later in his time in India. He became a merchant, financier and campaigner for social reform from his houses in Calcutta and Simla.

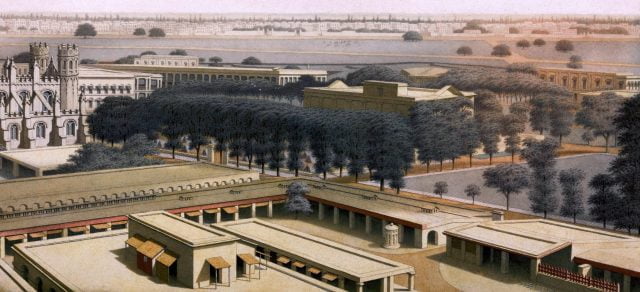

A Long Way From Home. View of the Interior of Fort William Calcutta (William Wood (fl. 1827–1833) cropped from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/de/Fortwilliam1828.jpg

As to the first, in the mid 1780s he was competing for contracts to supply his former service; he must already have had considerable resources behind him as one contract was to supply clothing for an entire brigade – about 3000 men.

For the second, he appears many times as an executor of the estates of dead colleagues, settling their Indian affairs and transmitting the cash realized back to heirs in the UK. He was in addition a director of the General Bank of India. It was perhaps ability in this sphere that led him to becoming a partner in a firm that was on the way to being the foremost of the first ever investment houses or banks – Paxton, Cockerell, Trail & Company, which before Philip’s death traded as Paxton, Cockerell & Delisle. The company arranged shipment of goods (tons of indigo, cloth, shellac), handled bonds drawn by merchants, contacted with the Government (or East India Company), hired vessels and much more. It’s worth noting that Sir William Paxton, a Berwickshire lad, who returned from India to run the British arm of the firm, died as one of the richest men of his age. What if Philip had lived?

Philip’s third interest was the condition of the many orphaned children left by his deceased colleagues. Early in 1782 he offered his house as a venue for a meeting of concerned military and company men. They initiated the Bengal Military Orphan Society and Philip was elected one of the six managers. The nascent society convinced Warren Hastings (the Governor General) and Sir Eyre Coote (CiC of the Company Army) to make universal subscriptions to the society an official deduction from the salary of all Company officers; the Society closed to new subscribers in 1861 but the institutions it started continued under the Raj. It may well be that Philip’s interest was personal. Because he was one of the many young men who had taken an Indian partner.

Philip thought he was well prepared when he died. His will makes ample provision for his siblings, his Indian partner (and her sister) and attempted to make full provision for his children by her: Philip, Mary, Thomas and a baby born after he died, Ann. While his executors worked to wind up his estate, the four youngsters were placed in the care of David Anderson of St Germains (by Longniddry) and brought from India to East Lothian with his entourage. They were deposited with their senior living Scottish relative, their aged step-grandmother, Mary Melvil Fall Delisle. It seems, despite Philip’s concern for fatherless children, that mother’s rights were not part of the plan; she remained in India. But once again, John Muir’s childhood home heard the chatter of young voices. Although accepted into the family, there was a sting in the tail. Whilst the men of British India were in the main accepting of their ‘natural’ children it was not universally so with their residual families in the UK.

Aunt Ann Plots a Doublecross

The children’s surviving aunt Ann Delisle and her husband Dr William Wightman (still down in Eyemouth) employed lawyers who found wriggle room in Philip’s will. The eventual case established legal precedent. It stripped the children of everything that Philip left that had accrued to him between the time of the will (1785) and his death (1788). So his two Indian houses and much of his cash went to his surviving sister, Ann Delisle, and not his children as he had intended. Of course, Ann didn’t quibble over the £1,500 Sterling she had been left in the will; she took that as well!

How much of this the children knew, then or later in life, we don’t know. They, like the earlier generation, grew up to make their way in the world and leave the house in Dunbar:

In 1809 Ann Delisle married James Hay, captain of an East Indiaman and later of a mail packet ship (sailing worldwide); they settled on the Isle of Man.

Her sister Mary Delisle married, in April 1800, Captain (afterwards Lieutenant General) John Ramsay, son of the 8th earl of Dalhousie; they settled in Edinburgh where she had large family. One of her sons inherited the earldom (George Ramsay, 12th earl of Dalhousie) and others rose high in Indian Administration and Imperial Service.

Thomas Delisle died unmarried in Dunbar in 1811.

Philip Delisle III followed his father and grandfather into the military and rose to the rank of major. He had worldwide postings during his career perhaps most significantly to Norfolk Island, the penal colony of the then penal colonies of Australia. But that’s another story.

Next Time

The next week we’ll carry on with the story of the Delisles and Wightmans, the building of John Muir’s Birthplace, and introduce another soldier into our story – one Daniel Muir.