Part 7 – The End of Dr Wightman

Now we consider what happened to Dr Wightman, who had left a roomful of chemistry apparatus in his house in Dunbar but who lived far away in Northumberland. And the Muirs make their moves.

The Travails of Dr Wightman

Title page of Charles Wightman’s ‘Treatise’ (from archive.org)

After he graduated from Edinburgh University and set up as a physician in Alnwick, Dr Charles Wightman seems to have prospered. He soon moved to Sunderland and then to Newcastle-upon-Tyne where he bought a fine house in a good location. Along the way he married (1822) Miss Janet Thomson, a daughter of the laird of Earnslaw in Berwickshire, and began a family. His inheritance was invested in property, land and the stock market – it’s fair to say he went potty about the railways that were being floated in the 1830s. He subscribed £5000 to each of at least 5 separate railway flotations (not all these came to fruition, so the same sum might be invested more than once)! In 1840 he published a Treatise of the Sympathetic Relation between the Stomach and the Brain, which indicates his professional interests.

But fortune turned. The early railway speculations were a bubble and many investors lost out – Dr Wightman amongst them. While his speculations were in play, his family was decimated by death. He lost his wife and several children until, in 1841, at his fine Georgian residence in Eldon Square, Newcastle, only he and his daughter Janet Thomson Wightman were left. A housekeeper and two other female servants completed the household. Dr Wightman made several public (and fawning) attempts to be appointed Physician to Newcastle Infirmary, but was never preferred. He tried for other public medical posts, without success. The Newcastle house, and land he had purchased speculatively, had to be mortgaged. It would seem on top of everything that money troubles were growing. Even the houses in Dunbar were sold. Robert Fall’s old house went to Daniel Muir in January 1842 and the ‘new built house’ (where John Muir was born) to Matthew Watt during 1846.

In 1847 a mortgage on the house in Eldon Square was transferred to a local painter and decorator (in lieu of debt?). By the census of 1851 Dr Wightman was resident in a lodging house in Princes Street, Newcastle; his landlady was his former housekeeper.

Dr Charles’ surviving daughter Janet, however, made a good match. In 1853 she married Alexander Christie-Thomson, controller of the Post Office Savings Bank, then on its way to becoming a national institution. But Dr Charles died in Newcastle during 1857. There was nothing left for Janet to inherit.

Daniel Muir Advances

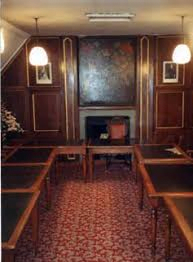

Re-imagined interior of John Muir’s first home (Image by CyArk for JMBT & Partners)

Daniel Muir arrived in Dunbar with a new wife, a lease on a house, and took over a struggling business. He lost the first, kept the second, and transformed the third.

A simple way to monitor Daniel Muir’s progress is to tap the opinion of the Session Clerk who compiled the Parish Register. Until David Muir was born in 1840, Daniel was described as ‘shopkeeper’ at the baptisms of his three earliest children; with David it became ‘mealmonger’; with Daniel junior ‘mealdealer’; and finally, with the twins in 1846, ‘merchant’. Daniel had made it in the eyes of Dunbar officialdom!

Sampler by Ann Gilrye, John Muir’s Mother. Courtesy of University of the Pacific Muir-Hanna Collection

As Daniel progressed though the ranks of Dunbar society, revolution was in the air. Years of burgess privileges had been swept away in the Reform Acts of the 1830s. For Daniel and his like minded friends in the Associate Presbyterian churches it meant enfranchisement for many. Whereas David Gilrye, Daniel’s father-in-law, had been eligible to sit on the burgh council simply because he was a burgess, Daniel was now eligible as a simple elector in a much expanded electorate. And stand he did.

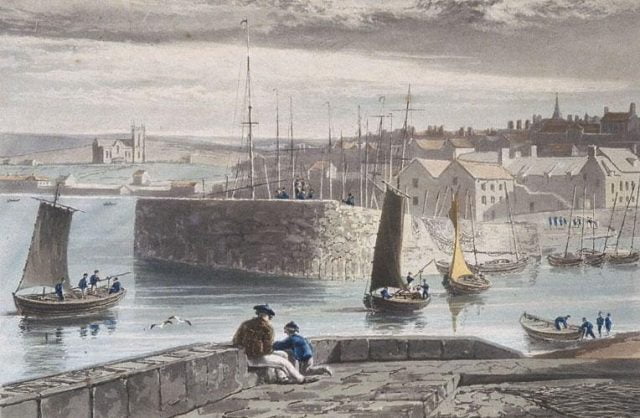

Council Chamber, Dunbar Town House

The council had been reduced to 12 elected members, 4 being elected (for a 3 year term) every October. It took some years for the ‘new men’ (it was still only men) to become a majority. When they did, the council went from Tory to Whig (Liberal). In October of 1847, when Daniel joined the council, Simon Sawers of Newhouse (a former civil administrator of Ceylon (Sri Lanka)) became provost (mayor) in the Liberal interest and Christopher Middlemass, who had dominated Dunbar politics in the Tory interest for the best part of 50 years, found himself an ordinary councillor sitting alongside the likes of Daniel Muir, John Mather (Ann Gilrye’s cousin), John Richardson (father of John’s friend Bob), and Robert Cossar the innkeeper, all newly enfranchised ‘new men’.

Daniel was obviously a good man to cultivate. With his rising status amongst the businessmen of the town, his reputation for ‘fair dealing and good measure’, his forthright Christianity and generosity to his chosen church he would be noticed. It would be noticed too that he had purchased ‘that large and commodious house’ that John remembered. Daniel had bought the house from Dr Wightman’s agents when the Doctor’s money needs became imperative in January 1842. But the evidence suggest that the family was already in occupation before that date.

The information is scanty – named household members, occupations, ages and an indication of birthplace – and addresses minimal, but it is clear that the Muirs (spelt Moore by the census taker) are in the big house. The gardener’s widow Catherine Nisbet, still in residence above the laundry on the north side of the garden, is named immediately before the Muir family. Dr Wightman, despite his own circumstances, took care to ensure that her liferent right to the cottage was written into the terms of the sale to Daniel. As the census shows that the ground floor of John’s birthplace next along the street was occupied by John Finlay and his family, Daniel had moved his growing business to the big house as well. A decennial census was taken on the night of 6th June 1841.

Courtesy of Dunbar and District History Society

Another snippet of evidence perhaps corroborates the Muirs’ occupation of the house prior to purchase and it comes from John Muir himself. John related that sister Sarah tipped little John off his stool such that he bit his tongue. Then he was rushed out the back way, through the garden to Peter Lawson, the apothecary. John estimated he was then around 2 ½ – say between October 1840 and January of the next year, when he started school. This can only have happened from the big house – there was no back route from the wee house.

The next change for John Muir’s childhood home came at the beginning of February 1849. Daniel Muir sold the house to Dr John Lorn. Daniel, Sarah, John and David began their journey to America before the end of the month. Ann and the rest of the children may have been in residence until they left in October, or they may have moved back in with her parents over the road. A new start for all.

Next – Muir Houses Through Time – Part 8 The Post Muir Years