Part 4 – An Avaricious Aunt

In the earlier parts we looked at the first family that built and lived in John Muir’s childhood home. We begin this chapter with a new family and their story.

The Second Family

After marrying her soldier John Barton, Janet Fall seems to have split her time between Dunbar and Ireland. She was still in Dunbar in 1752 when she became a founding investor in the Lothian and Merse Whale Fishing Company, the latest scheme of her cousins in the family business. She was back again in 1758. Sadly, John’s death was recorded at Dunbar on the 17th of July, which seems to have prompted Janet to write her own will, registered in November 1758. This may have been in part to sort out her mother’s security. Janet still owned the house but her mother and her new step family were now the principal residents. Janet never met the next group to arrive: she died in Ireland during 1768.

Captain Philip Delisle continued as a serving officer, so his second wife Mary Melvil Fall must have been left with her hands full looking after her step-children Elizabeth, Philip junior and Ann Delisle. There were nursemaids and servants to help but still, feeding, clothing and schooling the children must have kept Mary busy. She did well and all three reached adulthood. They began to make their way in the world:

Elizabeth Delisle married Thomas Meek in September 1779. Thomas was a local merchant, much involved in the management of the Whale Fishing Company. The couple remained in Dunbar where Elizabeth died in 1791.

Philip Delisle junior joined the East India Company’s army in Bengal. He was dead by 1788, but therein lies a tale!

Ann Delisle eloped with Dr William Wightman of Eyemouth. Their irregular marriage was registered at Haddington in August 1782. They settled in Eyemouth where William practised and his brother Charles Stewart Wightman was a prominent merchant and more!

Philip junior’s Tale

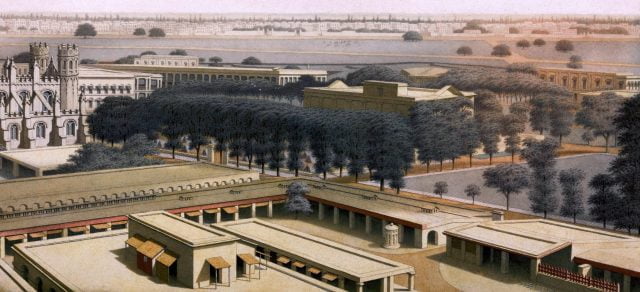

We’ll take some time to look at Philip’s tale, as it bears on the later house history. In 18th century Scotland the British East India Company, the semi-government institution that monopolised Britain’s trade with the sub-continent, was seen as a wonderful career opportunity for adventurous young men. The plum administrative positions with the company were the very devil to get. It needed connections and political influence to secure even a minor clerkship. But there was another, much easier way. There were always openings in the Company’s armies, such was the attrition of the officer corps through disease, debilitation and death – comparatively few died in battle. But if chance allowed survival, there were opportunities aplenty. That’s the route young Philip took. As yet we know nothing of his military career except that, like his father, he reached the rank of captain. Between 1775 and 1782 he was deputy Paymaster to the 1st Brigade of the Company’s Army stationed at Fort William, Calcutta. His activities become much clearer later in his time in India. He became a merchant, financier and campaigner for social reform from his houses in Calcutta and Simla.

A Long Way From Home. View of the Interior of Fort William Calcutta (William Wood (fl. 1827–1833) cropped from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/de/Fortwilliam1828.jpg

As to the first, in the mid 1780s he was competing for contracts to supply his former service; he must already have had considerable resources behind him as one contract was to supply clothing for an entire brigade – about 3000 men.

For the second, he appears many times as an executor of the estates of dead colleagues, settling their Indian affairs and transmitting the cash realized back to heirs in the UK. He was in addition a director of the General Bank of India. It was perhaps ability in this sphere that led him to becoming a partner in a firm that was on the way to being the foremost of the first ever investment houses or banks – Paxton, Cockerell, Trail & Company, which before Philip’s death traded as Paxton, Cockerell & Delisle. The company arranged shipment of goods (tons of indigo, cloth, shellac), handled bonds drawn by merchants, contacted with the Government (or East India Company), hired vessels and much more. It’s worth noting that Sir William Paxton, a Berwickshire lad, who returned from India to run the British arm of the firm, died as one of the richest men of his age. What if Philip had lived?

Philip’s third interest was the condition of the many orphaned children left by his deceased colleagues. Early in 1782 he offered his house as a venue for a meeting of concerned military and company men. They initiated the Bengal Military Orphan Society and Philip was elected one of the six managers. The nascent society convinced Warren Hastings (the Governor General) and Sir Eyre Coote (CiC of the Company Army) to make universal subscriptions to the society an official deduction from the salary of all Company officers; the Society closed to new subscribers in 1861 but the institutions it started continued under the Raj. It may well be that Philip’s interest was personal. Because he was one of the many young men who had taken an Indian partner.

Philip thought he was well prepared when he died. His will makes ample provision for his siblings, his Indian partner (and her sister) and attempted to make full provision for his children by her: Philip, Mary, Thomas and a baby born after he died, Ann. While his executors worked to wind up his estate, the four youngsters were placed in the care of David Anderson of St Germains (by Longniddry) and brought from India to East Lothian with his entourage. They were deposited with their senior living Scottish relative, their aged step-grandmother, Mary Melvil Fall Delisle. It seems, despite Philip’s concern for fatherless children, that mother’s rights were not part of the plan; she remained in India. But once again, John Muir’s childhood home heard the chatter of young voices. Although accepted into the family, there was a sting in the tail. Whilst the men of British India were in the main accepting of their ‘natural’ children it was not universally so with their residual families in the UK.

Aunt Ann Plots a Doublecross

The children’s surviving aunt Ann Delisle and her husband Dr William Wightman (still down in Eyemouth) employed lawyers who found wriggle room in Philip’s will. The eventual case established legal precedent. It stripped the children of everything that Philip left that had accrued to him between the time of the will (1785) and his death (1788). So his two Indian houses and much of his cash went to his surviving sister, Ann Delisle, and not his children as he had intended. Of course, Ann didn’t quibble over the £1,500 Sterling she had been left in the will; she took that as well!

How much of this the children knew, then or later in life, we don’t know. They, like the earlier generation, grew up to make their way in the world and leave the house in Dunbar:

In 1809 Ann Delisle married James Hay, captain of an East Indiaman and later of a mail packet ship (sailing worldwide); they settled on the Isle of Man.

Her sister Mary Delisle married, in April 1800, Captain (afterwards Lieutenant General) John Ramsay, son of the 8th earl of Dalhousie; they settled in Edinburgh where she had large family. One of her sons inherited the earldom (George Ramsay, 12th earl of Dalhousie) and others rose high in Indian Administration and Imperial Service.

Thomas Delisle died unmarried in Dunbar in 1811.

Philip Delisle III followed his father and grandfather into the military and rose to the rank of major. He had worldwide postings during his career perhaps most significantly to Norfolk Island, the penal colony of the then penal colonies of Australia. But that’s another story.

Next – Muir Houses Through Time – Part 5 Inheritance and ‘The New Built House’